Winning starts with what you know

The new version 18 offers completely new possibilities for chess training and analysis: playing style analysis, search for strategic themes, access to 6 billion Lichess games, player preparation by matching Lichess games, download Chess.com games with built-in API, built-in cloud engine and much more.

On Sunday, December 26, 2004 at 7:58:53 a.m. local time the fourth largest earthquake in the world since 1900 occurred off the west coast of northern Sumatra. The resulting tsunami caused more casualties than any other in recorded history, killing more than a quarter of a million people.

Some time after the disaster had struck we published a report on it, not least because many of our readers requested we do so, despite the absence of a direct chess link. Since then we have received a steady stream of letters on the subject, and today we return to the subject in a more scientific vein.

One early letter which stood out was from John Nunn, mathematician, grandmaster, chess publisher, who is very knowledgeable on any subject connected with science in general. John wrote:

"I think this whole Indian Ocean Tsunami disaster demonstrates how badly people assess risks involving rare but catastrophic events. There is a consistent error in such assessments: risks involving human agencies are regularly over-estimated, while risks involving natural agencies are regularly under-estimated. Thus the following risks are over-estimated:

The following risks are under-estimated

It is depressing to consider the vast amounts spent on anti-terrorism measures (including the Iraq war), many of them quite pointless, while a few million dollars would have provided a tsunami warning system which would probably have saved a huge number of lives."

This letter struck a note (and drove us to write this article). For some years I myself have been posing the following question to friends and associates: Which of the following events should we be most afraid of:

After a while I usually pass out a "hint": one of the above disasters is infinitely more devastating and capable of killing orders of magnitude more people than the other four. It is also very much more likely to occur. And finally there is, in the foreseeable future, absolutely nothing we can do about it. We will come back to the subject below.

Will the world as we know it end on Garry Kasparov's 66th birthday? This question is not as flippant as it looks. In fact for a few days at the end of last year it looked like a very distinct possibility that an asteroid could impact Earth on that day. According to NASA it would strike with an energy of about 1400 megatons of TNT, 25 times more than the largest thermo-nuclear bomb ever tested and about 100 times more powerful than the Tunguska explosion over Siberia in 1908.

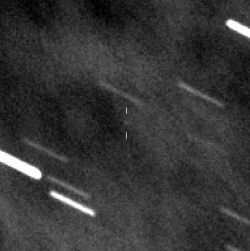

Hard to see: 2004 MN4 in a telescope image |

2004 MN4 is the unimaginative name given to a large rock – or small asteroid – that is moving in Earth-crossing orbit. It is estimated to be 400 meters (1300 feet) in length and to have a mass of around one million metric tons. 2004 MN4 was discovered in June 2004 by astronomers at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona. They observed it for two nights. The object was rediscovered on December 18 in Australia, after which first calculations of a possible Earth impact could be made.

On December 24 NASA published an impact chance figure of "around 1 in 62" (or 1.6%), the highest probability for any asteroid ever observed. In the course of a week NASA corrected the estimate on the basis of more observations to 1 in 37 or 2.7%.

Subsequently the asteroid was precovered (discovered on older photographs). In addition, NASA has just finished conducting radar measurements with the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico. The result of the new calculations is a zero percent chance of Earth impact. 2004 MN4 will pass the earth at a distance of 36,350 km (or 22,600 miles), which is closer to the planet than geosynchronous satellites that relay TV and communication signals. The flyby will occur on April 13, 2029, which coincidentally is a Friday (paraskavedekatriaphobes can find relief here) and, even more ominously, Garry Kasparov's 66th birthday! [When we told him about NASA's latest findings Garry expressed relief: "Thank heavens. You know that people would have blamed it on me!"]

On April 13 2029 the rock will be easily visible to the naked eye, having a magnitude of 3.3. You will be able to see it at around 11 p.m. in Europe, moving past the constellation of Gemini at a rate of 42° per hour, which is less than half as fast as the International Space Station moves across the sky.

It should be noted that all impact estimates rely on a complete knowledge of the inner solar system and all the interactions that 2004 MN4 will have from now until the year 2029. Unfortunately this knowledge is far from complete, and even a tiny change in the path of the rock, due for instance to an encounter with an unknown object, will produce a substantial variation in the final earth-crossing position.

Currently there are 671 known asteroids with earth-crossing orbits. These are being tracked by NASA's Near Earth Object Program. None is considered potentially hazardous to earth in the near future.

In the follow-up to the original fairly dire risk calculations published by NASA, John Nunn retracted "asteroid impacts" from his list of humanity-threatening natural disasters. "Thinking about it a bit more, I don't think there is much danger from an asteroid impact. I had thought about the 1908 Tunguska impact, equivalent to perhaps a 10-megaton hydrogen bomb. Assuming one impact a century, this sounds quite dangerous. But if you assume that the impact kills everyone in an area of a thousand square kilometres, then, with surface area of Earth = 500 million square kilometres, that would be about 12 people per square km. Thus the impact kills 12,000 people or 120 per year. Thus it isn't much of a danger at all, compared for instance to epidemics, which are far more of a danger than the others."

A web page entitled "The Odds of Dying" (have a few hours free if you go here) gives precise figures: the lifetime odds for dying of heart disease is 1 in 5, of cancer 1:7, stroke 1:23, car accidents 1:100, firearms 1:325, air travel 1:20,000, lightning 1:83,000, earthquake 1:132,000, asteroid impact 1:200,000 and Tsunamis 1:500,000.

The devastating Indian Ocean Tsunami of December 26, 2004, has caused well over 250,000 deaths. But how does it compare to other natural disasters in recent history? Here are a few statistics:

2003: An earthquake in Bam, Iran, officially killed 26,271

1976: An earthquake in Tangshan, China, killed 242,000

1970: A cyclone in Bangladesh killed 500,000

1923: The Tokyo earthquake killed 140,000

1887: China's Yellow River broke its banks in Huayan Kou killing 900,000

1826: A tsunami killed 27,000 in Japan

1815: A volcanic eruption of Mount Tambora on Indonesia's Sumbawa Island killed 90,000

1556: An earthquake in China's Shanxi and Henan provinces killed 830,000

Let us return to Tsunamis. Devastating as the December 26 tidal wave was, it pales to insignificance compared to some of the geological time-bombs that are slumbering around the globe. These can release mega-tsunamis, more destructive than anything we have witnessed in mankind's history. And the next episode is likely to emanate from the balmy Canary Islands off the coast of North Africa, causing a wall of water to cross the Atlantic Ocean with the speed of a jet airliner and devastate the East Coast of the United States.

Mega-tsunamis are generally landslide-generated. The greatest danger comes from large volcanic islands which are prone to massive landslides. For instance the sea floor around Hawaii is covered with the remains of truly colossal landslides that occurred millions of years ago. Fortunately, such events are very rare, but concern is growing that ideal conditions for such a landslide currently exist – on the island of La Palma in the Canaries. During a 1949 eruption of the southern volcano, Cumbre Vieja, a gigantic fissure appeared across the side of the volcano, and the western half slipped a few metres towards the Atlantic before stopping in its tracks.

Schematic by the Universidad de Barcelona

Scientists believe that the western flank of the volcano might give way completely during a future eruption, causing a mass of around 500 thousand million tonnes to slide into the Atlantic Ocean. This would generate an almost inconceivably destructive wave, which would surge across the entire Atlantic in a few hours. The worst case scenario envisages an initial bulge of water 900 meters high. This subsides to form waves in excess of 100 m in height that strike neighbouring islands. After an hour waves 50 to 100 m high hit the Northwest African coast. Spain and the UK experience waves 7 to 10 m high, two to five hours after the collapse. After nine hours, the Florida coastline can expect to face around a dozen waves between 20 and 25 m high. It would engulf the East Coast of the US, sweeping away everything up to a distance of 20 km inland.

Which brings us back to our little quiz at the top of this page: which disaster should we fear most? The correct answer, as many of you might have suspected, was Yellowstone National Park. It turns out that this famous tourist attraction, visited by millions each year, is a so-called "super-volcano", one thats eruption would be unlike anything we have ever witnessed – at least in the last 75,000 years.

Super-volcanoes are created when magma creates a giant reservoir in the Earth's crust. It increases to an enormous size, building up colossal pressure until it finally erupts. This happens on a "mega-colossal" scale (scientists classify volcanic explosions as gentle, explosive, severe, cataclysmic, paroxysmal, colossal, super-colossal and mega-colossal). The explosion would cover the North American continent with many inches of ash and debris, bringing all life to a standstill. And it would send ash, dust, and sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere, which would circle the Earth, darkening the skies for a number of years, causing temperatures to plummet. Many species of animals and plants would face extinction. The last time a super-volcano blew, Toba 74,000 years ago in Sumatra, it reduced the human population on Earth to just a few thousand individuals. Mankind was pushed to the edge of extinction.

The good news is that Yellowstone has a fairly stable eruption cycle of 600,000 years. The bad news: the last eruption was 640,000 years ago.