Winning starts with what you know

The new version 18 offers completely new possibilities for chess training and analysis: playing style analysis, search for strategic themes, access to 6 billion Lichess games, player preparation by matching Lichess games, download Chess.com games with built-in API, built-in cloud engine and much more.

Ultimately chess is just chess - not the best thing in the world

and not the worst thing in the world, but there is nothing quite like it.

– W.C. Fields

In part 2 of our series “A great moment in chess”, we followed the Fischer-Spassky World Championship Match of 1972 to the conclusion of Game 1 which Spassky won. There was immense international interest in the match with front page coverage from many of the world's well-known newspapers and magazines.

Fischer attributed his loss in Game 1 to the disturbance resulting from the presence of film cameras in the playing hall. After the game he demanded from the Icelandic Chess Federation that he be given complete control over the filming in the hall. They refused. And indeed, legally there wasn’t much they could do, since the filming rights had been sold to the American businessman Chester Fox.

There was intense negotiation going on between Fischer's lawyers, the Islandic Chess Federation and the Chester Fox team. All this behind the scenes. Without resolution of the central issue.

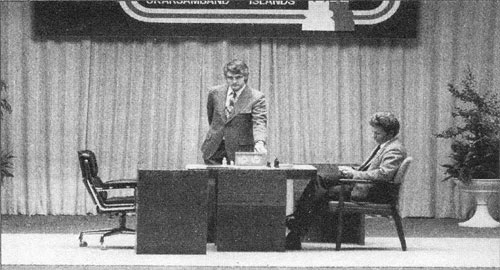

According to the match schedule, Game 2 was to begin at 5:00 p.m. on Thursday, July 13, with Fischer playing the white pieces. The German referee, Grandmaster Lothar Schmid, starts Fischers clock at exactly this point in time. Spassky had arrived a few minutes earlier and was sitting at the table.

Fischer, however, was still in his hotel room. The challenger had one hour to appear at the board and make his first move otherwise he would lose that game by forfeit. In an attempt to accommodate Fischer's demands, the organizers had tried to position the cameras in a way they could not be seen. They were hidden in black towers with little 4-inch holes in them for the lenses. These lenses were not visible from the playing table and also no camera noise could be heard there. Before the game, Referee Schmid had inspected this set-up and was thoroughly satisfied. To the chief organizer of the match, Gudmundur Thorarinsson, he stated: “If Bobby will object to this, I will rule against him.”

At 4:50, ten minutes before Schmid presses the clock for Game 2, Thorarinsson informs one of the lawyers for Chester Fox that Schmid was satisfied with the arrangements for the cameras. This information was also transmitted to Fischer in his hotel room. Fischer, in anger, yelled that he wouldn’t appear for the game. One of Fischers spokesmen, Fred Cramer, approached Schmid, asking him to delay the start of the game to resolve the camera issue. Schmid refused, indicating that the match rules did not allow this.

At exactly 5:00 p.m. Fischer's clock starts ticking. With Fischer showing no intention to appear at the board, tension starts to increase among the officials in the hall. At 5:10 Thorarinsson phones Fischer's hotel suite and talks to his second William Lombardy, who is with Fischer. Thorarinsson asks that Fischer at least come to the hall and play the game under protest.

At 5:15 Paul Marshall, Fischer's lawyer in Reykjavik, pleads with Schmid to stop Fischers clock to have time for further negotiations. Schmid refuses: “If Bobby does not come, I have to declare a forfeit.”

At 5:20 Thorarinsson confers with Chester Fox and his lawyer Richard Stein.They decide to hold their position. Still, Thorarinsson is well aware that most likely it will put an end to the match if Fischer is forfeited on Game 2. He says to Fox: “We must not show the slighest weakness now. Our only chance to win is to convince Bobby that we will give up the match rather than give in. But between ourselves, we must understand that if Bobby is crazy enough to hold out, we will have to give in first.”

At 5:30, Andrew Davis, another of Fischer's lawyers urgently phones Richard Stein from New York and pleads with him: “Dick, you've got to help us. Fischer is in a stubborn rage and we need at least a day to cool him down. If you can pull the cameras out for this game, I'll do my goddamnest to help you. Otherwise, it's all over. He won't accept a forfeit.” Stein, being left with no other options, agrees instantly, and convinces Thorarinsson that Fischer was indeed ready to wreck the match over the cameras. It was 5:35 by now. Thorarinsson phones Lombardy, telling him that he was ordering the cameras out. Lombardy transmitts this information to Fischer. “Bobby says he'll come.”, Lombardy tells Thorarinsson. There is an avalanche of relief among organizers and match officials in the playing hall. The situation seems to having been saved almost at the last moment. It is 5:39. Fischer has 21 minutes to appear to make his move. During all of the wheelings and dealings behind the scenes, a police escort, engine running, has been waiting outside Fischer's hotel and all traffic lights on the way to the playing venue were held at “green”. In addition, the road between Fischer's hotel and Laugardallshall is cleared of traffic – protocoll for a head of state. And it is only a few minutes drive. But then Fischer adds one more condition. He wants his clock set back to zero!! Thorarinsson's eyes went wide in this rollercoaster ride. Only the referee has the authority to reset the clock and Thorarinsson immediately approaches Schmid with Fischer's demand. But Schmid refuses. In a later interview he says: “If Mr. Fischer had come to the playing hall, I could have helped him. But he did not come, and his protest was not valid. I had no choice but to start his clock. It cannot be set back.”

Thorarinsson goes back to the phone and reports Schmids decision to Lombardy in Fischer's suite. In the mean time, the Islandic Grandmaster Olafsson has been sent to Fischer's hotel, also to try to convince Fischer to come. He found Fischer in a titanic rage, pacing the room back and forth.

It is 5:47 when Olafsson himself places a phone call to Lothar Schmid, telling him that the point was reached when only he could save the match: “Speak to Boris, Lothar. Ask him if he will agree to restart the clock.” But Schmid sticks to his decision. “I cannot. Bobby has 12 minutes. I suggest he come.” When Olafson transmitted Schmidt's reply to Fischer, he tore the phone cord out of the wall.

At exactly 6:00 p.m., Lothar Schmid steps to the playing table and stops Fischer's clock. With a somber voice, he informs the disappointed audience: “Ladies and Gentleman. Mr. Fischer did not appear in the playing hall. According to Rule Nr. 5 of the Amsterdam Agreement if a player is one hour late, he loses the game by forfeit.”

Most of the people involved with the match were in a state of depression. It seemed all over.

About

the author

About

the authorChristian Hesse holds a Ph.D. from Harvard University and was on the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley until 1991. Since then he is Professor of Mathematics at the University of Stuttgart (Germany). Subsequently he has been a visiting researcher and invited lecturer at universities around the world, ranging from the Australian National University, Canberra, to the University of Concepcion, Chile. Recently he authored “Expeditionen in die Schachwelt” (Expeditions into the world of chess, ISBN 3-935748-14-0), a collection of about 100 essays that the Viennese newspaper Der Standard called “one of the most intellectually scintillating and recommendable books on chess ever written.”

Christian Hesse is married, has a six-year-old daughter and a two-year-old son. He lives in Mannheim and likes Voltaire's reply to the complaint: ”Life is hard” – “Compared to what?”.

Previous articles for ChessBase: